Fighting climate change in Africa - with fire

Posted on 4 November 2015

Controlled fires could help to save one of the world's last great wildernesses, according to our biologists

After rain, I have seen burned areas beginning to turn green in a week – it’s like spring speeded up”

Some of our early ancestors were the first to discover the benefits of burning the savannah grasslands in East Africa as a way of creating grazing and keeping the encroaching bush at bay.

Ecologist and savannah specialist Dr Colin Beale from our Department of Biology thinks it's an idea worth rekindling for a more immediate problem. He is leading a major international research project studying fire as a method of tackling the effects of overgrazing and climate change on the savannah, an area that includes some of the world's most important ecosystems.

Weather patterns

Dr Beale says the savannahs are the victims of shifting weather patterns which mean that although the overall amount of rain is the same, it now falls in shorter, more extreme bursts making it more difficult for grasses to absorb nutrients. The grass is then less nutritious for grazers and less attractive to insects, an important food source for native bird species.

At the same time, the number of people living in savannah landscapes is growing. This increased population is less migratory, as they develop stronger community bonds to schools, health services and resources. Livestock grazing patterns also become more fixed, causing overgrazing on areas of already degraded land.

Environmental stress

“The result is environmental stress – in some areas of Tanzania you can drive for tens of kilometres through land that is completed degraded and unable to support wildlife or cattle," he says. "That’s a real issue for people trying to live in that landscape."

Dr Beale admits that burning areas of land that are already barren and unproductive might seem like a blunt instrument, but fire is one of few land management options available for a wilderness on the scale of the vast East African plains.

“It’s just not practical to drop fertilisers from a plane onto an area this size, but fires can burn on a large scale and the burn does encourage new growth. After rain, I have seen burned areas beginning to turn green in a week – it’s like spring speeded up.

“Without human intervention, savannahs can easily become impenetrable scrub land. Fire is one land management tool we can use to tackle this,” says Dr Beale.

A particular focus for his research is the iconic Serengeti, home of the indigenous Maasai people and the site of spectacular annual animal migrations. The research, known as the Serengeti Fire Management Project, is examining the knock-on effects of climate change, wildlife and human population trends on this internationally important landscape.

The three-year study is funded by the Leverhulme Trust and includes experts from Princeton University and the University of Cape Town as well as East African governmental organisations.

As well as studying the size and the nature of the problems afflicting stressed savannah plains, Dr Beale is part of a major international project testing practical solutions on the ground.

Trial plots

He returns to northern Tanzania later this year to work on the development of a series of trial plots which will test different land management techniques, including burning.

“We are working with local communities to look at how we can ‘re-set’ the land using different grazing patterns and restoration techniques. Controlled fires will be part of the study,” says Dr Beale.

Funded by US Government development agency USAID, the project is part of a wider effort to help East African communities adapt to climate change.

Dr Beale’s research is helping to understand and quantify the problems facing the African plains, but that fundamental insight is also informing the applied work on the trial plots. It’s a perfect example of fundamental science in action, he says.

“As a scientist, my interest is in the nuts and bolts of what makes a savannah ecosystem tick, why the landscape looks the way it does and how it supports such a wide range of animals.

“That understanding also has the potential to translate into practical help for the communities who live there. If the rains fail, many indigenous people such as the Maasai are only one year away from serious trouble. Our aim is to use science to make the savannah more resilient and make the way of life for native people more secure, easing the worry that the next drought could be the one that could kill them.”

The text of this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence. You're free to republish it, as long as you link back to this page and credit us.

Dr Colin Beale

Research interests range from population dynamics and distributions to fire ecology in the African savannah

Explore more research

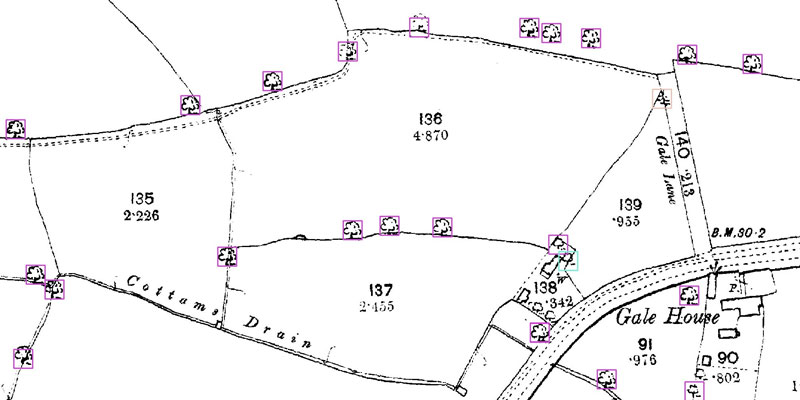

A research project needed to spot trees on historic ordnance survey maps, so colleagues in computer science found a solution.

We’re using gaming technology to ensure prospective teachers are fully prepared for their careers.

A low cost, high-accuracy device, could play a large part in the NHS's 'virtual wards'.