Heat or eat? The stark choice facing some low income families in rural areas

-

Research

- Justice and Equality

Posted on 21 March 2016

Big decisions about small amounts of money: our social policy experts uncover the grim reality of rural poverty in England

You don’t expect to see the level of poverty we discovered in the UK”

“We got to the point where the cupboards were totally and utterly empty… It was embarrassing as hell. I had to take him up to school and ask the headmistress, the teacher, if they could provide my son with a packed lunch because I didn't even have anything in the cupboard to do that.”

‘Peter’s’ story is highlighted in a pilot study by researchers at York who laid bare the harsh reality of life on a low income in rural England.

And their work shows that Peter's experience is not an isolated one.

“It’s a big concern that there are people in the UK today who don’t have enough food in the house or can’t heat their homes,” says Dr Carolyn Snell from our School for Business and Society who co-authored the study. “We found that low income households have to prioritise and ration their spending in complex ways.”

Food banks

Working with researchers from the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute, the team interviewed householders attending food banks in the South West of England. They wanted to understand how people on low incomes in rural communities manage to balance limited budgets and what influences the difficult spending decisions householders are forced to make.

The project uncovered evidence of people caught up in a perfect storm of austerity, benefit cuts, low paid jobs and cuts to local authority services.

For many, it's a stark choice between food and fuel. Most prioritise food over energy and within their limited choice of tough budgeting options, difficult decisions are made about the amount of energy used for basics such as lighting, cooking and hot water.

Heating is often regarded as an unaffordable luxury with the resulting cold, damp rooms causing health problems.

Money left for meals is often spent on the cheapest foods, or supplemented by supplies from food banks.

Budget dilemmas

Dr Snell explains: “These are just some examples of the types of choices made on a daily basis by families on low incomes. We’re one of the world’s richest nations and it’s important to question why some householders have to deal with these dilemmas.”

One interviewee told the researchers: “It means deciding whether to have the lights on and some heating on - or eating. That’s literally it. That is my life struggle, basically.”

Another said: “I have sat there with loads of jumpers on and you can see your breath… but I would rather have food than heat. As long as you have got food inside you then you are heating yourself because you have got fuel.”

The study found that food and fuel are the ‘elastic’ elements of household expenditure which often lose out to fixed costs such as rent and council tax.

“People might only heat one room – or if they have shared childcare arrangements, they might only heat their home on the days their children are in the house,” says Dr Snell. “There’s a question about, as a country, if we think that’s where we want to be.

Health

“But there also broader public health issues. If people are not heating their homes that can cause issues around child development or health conditions such as asthma. It can cause health problems for elderly people. Adolescents suffer higher rates of depression in cold homes.”

The research shows that poverty is often worse in rural areas where insecure seasonal employment, limited public transport, higher food costs and a lack of affordable housing all add to the problems.

“If you live in a rural area you do seem to be more vulnerable. Energy and transport can be more expensive and affordable food might be more difficult to get,” says Dr Snell. “Cuts in local authority support services and transport subsidies are having a particular impact on rural communities.”

Friends and family

The report also stresses the importance of a ‘buffer’ - a support network of family or friends who can help out in difficult times.

Sometimes people need family and friends so they can borrow money for food, electricity or petrol. But often the support is a meal, access to the internet, or a hot bath.

“I’ll just leave the house for a couple of days and go stay at a friend’s house until I can afford to get electric,” one food bank user told the researchers.

“Having a buffer can be what makes you more or less vulnerable, particularly in rural areas where people might be more isolated from friends and families,” says Dr Snell.

As part of the project, the research team also spoke to local authority officials and support organisations such as Citizens Advice. They also examined national statistics on living and food costs.

Rural poverty

“You don’t expect to see the level of poverty we discovered in the UK,” says Dr Snell. “It’s a particular problem in rural areas compounded by the fact that rural communities are often missing from national debates about poverty.

“Policymakers need to address the unique challenges facing the rural poor. The social and health costs of not addressing the root causes of food and fuel poverty could be substantial and raise questions about the type of society we want to live in.”

This research was funded by the Culture & Communities Network+

The text of this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence. You're free to republish it, as long as you link back to this page and credit us.

Dr Carolyn Snell

Research interests in energy policy in the UK, with a particular interest in fuel poverty

Discover the details

Read the report: Heat or Eat: Food and Austerity in Rural England

Read coverage of the report in the Yorkshire Post

Watch this video from The Guardian website: I live in real poverty, and it's not what you think

BBC One Panorama investigate fuel poverty

Visit the School

Explore more research

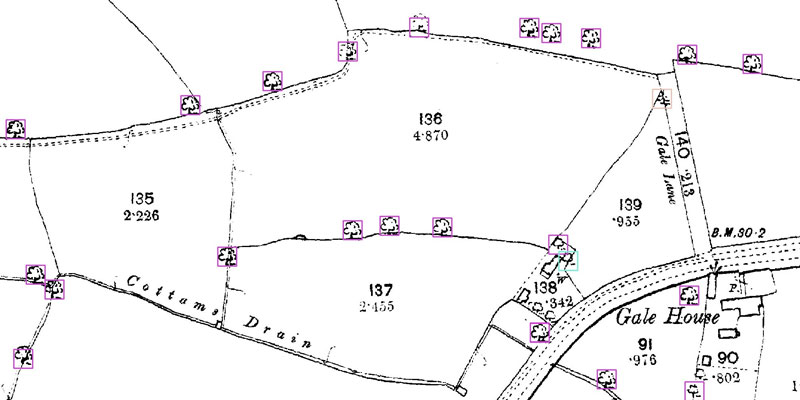

A research project needed to spot trees on historic ordnance survey maps, so colleagues in computer science found a solution.

We’re using gaming technology to ensure prospective teachers are fully prepared for their careers.

A low cost, high-accuracy device, could play a large part in the NHS's 'virtual wards'.