Leader of the pod: Menopausal killer whales hold key to family's survival

Posted on 11 March 2015

Female killer whales survive after the menopause so they can help their families by leading them to food, according to researchers in our Department of Biology.

... the benefits of older females knowing when and where to find salmon could be considerable,”

The study provides fresh insight into why women continue to live long after they can have children.

Most animals die at around the same time as they stop reproducing. Killer whales are one of just three species – alongside humans and short-finned pilot whales – where females continue to live for many years after giving birth to their last baby. It’s an evolutionary trait which has baffled scientists for years.

Hard times

But now a study, involving Dr Daniel Franks at York, has found that older female killer whales use hard won ‘ecological knowledge’ to lead groups of younger whales to salmon foraging grounds, especially during hard times when food is in short supply.

“Shortage of salmon is a major contributory factor to mortality in resident killer whales, so the benefits of older females knowing when and where to find salmon could be considerable,” said Dr Franks, a Reader in our Department of Biology and a member of the York Centre for Complex Systems Analysis.

The study also found that killer whale mothers were more likely to lead their sons than their daughters.

“Killer whale mothers direct more help towards sons than daughters because sons offer greater potential benefits for her to pass on her genes,” said Dr Franks. “Sons have higher reproductive potential and they mate outside the group, thus their offspring are born into another group and do not compete for resources within the mother’s group.”

The researchers studied data from killer whales off the coast of British Columbia and Washington. Dr Franks worked alongside experts from the University of Exeter and the Center for Whale Research (USA).

Evolution of the Menopause

The research is published in Current Biology. It is just one of the latest insights to emerge from a £500,000 project funded by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) looking at the evolution of the menopause in non-human mammals. Previous studies have shown that menopausal killer whales greatly increase their children’s and grandchildren's chances of survival. But how they helped their relatives to survive has remained a mystery - until now.

Dr Franks said the project casts new light on the evolution of human menopause.

"Sharing of information was potentially important for the evolution of menopause in humans. The written word didn't exist for almost the entirety of human evolution, and so information was therefore stored in individuals. The oldest more experienced people would know, for example, when and where to find food, and would be the most likely to have experienced times of hardship.

“This idea that post-menopausal women store ecological knowledge is difficult to test in humans, so the killer whales are a nice model for this as a highly social and kin structured species."

The text of this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence. You're free to republish it, as long as you link back to this page and credit us.

Dr Dan Franks

Research Title: Reader in the Departments of Biology and Computer Science

Research interests in evolutionary computation, coevolution, genetic algorithms, agent-based modelling, social network analysis, evolving game intelligence, games for science.

Discover the details

Find out more in the York Research Database

Publications

- Current Biology

Projects

Visit the departments

Explore more research

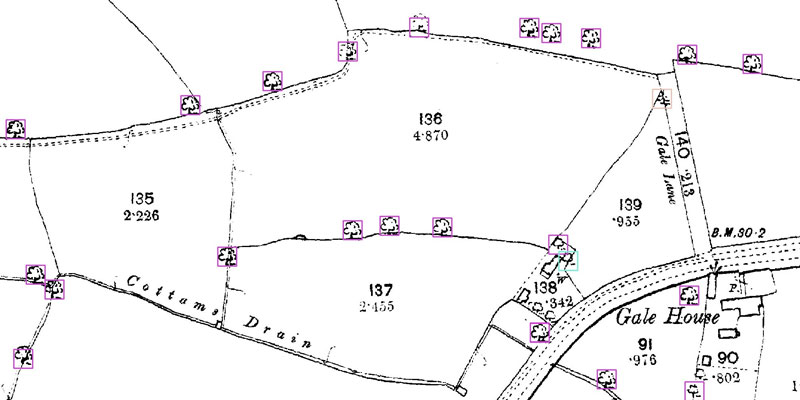

A research project needed to spot trees on historic ordnance survey maps, so colleagues in computer science found a solution.

We’re using gaming technology to ensure prospective teachers are fully prepared for their careers.

A low cost, high-accuracy device, could play a large part in the NHS's 'virtual wards'.