How to get ahead in cranial surgery

Posted on 6 July 2018

Computer scientists team up with surgeons at Alder Hey Hospital to create a groundbreaking cranial reconstruction tool

Dr Nick Pears with one of the Liverpool-York Head Model images.

Even if only a part of the skull or face is intact, the model could be used to reconstruct what the rest of the face or skull should look like... It's very exciting, it is the only model of its kind that currently exists and there's a huge amount of interest in it.

Researchers in our Department of Computer Science have played a key role in enabling surgeons to accurately carry out reconstructive cranial surgery, potentially revolutionising treatment for children with abnormally shaped heads.

Dr Nick Pears has worked with craniofacial surgeon Christian Duncan, head of surgery at Alder Hey Children’s Hospital in Liverpool, to create an interactive, three-dimensional model of a ‘normal’ human head, which surgeons can use as a reference point when carrying out reconstructive surgery.

Leading

Mr Duncan is one of the UK’s leading authorities on craniosynostosis - a condition caused when the plates of a baby’s skull fuse together too quickly, which, if left untreated, can cause breathing problems, headaches caused by pressure on the brain and cranial abnormalities which can lead to bullying and low self esteem.

Prior to Dr Pears’ involvement, the team at Alder Hey had undertaken a project they called "Headspace", in which they scanned 1,500 ‘normal’ male and female human heads, each from five different angles with a 3D camera. They were then faced with the question of how to turn this extraordinary library of scans into something that surgeons could use in their work.

Headspace

The answer came almost by chance. After seeing an item on the news in which Mr Duncan was talking about his "Headspace" project, Dr Pears knew he could help. He called Alder Hey, and the collaboration began.

That was four years ago. Dr Pears worked with Dr Will Smith and research student Hang Dai in the Department of Computer Science, as well as colleagues at Alder Hey to develop the "Liverpool-York Head Model" (LYHM).

Dr Pears explains: “The model allows surgeons to call up a range of ‘normal’ human heads shaped on a computer screen, then rotate and study them from every angle,” The models can be adjusted to take account of age and sex and even, to a limited degree, ethnicity.”

Planning

At present the LYHM is mainly used in planning and preparing for surgery, and also in assessing the success of an operation - and, says Christian Duncan, that last point is critical, because it gives surgeons an objective standard against which to measure their work.

“It’s unique,” says Mr Duncan. “It’s the only tool we have that lets us say ‘yes, that head is in the normal range’ and that’s important because it means success or failure can be objectively measured - vital for prospective patients and their families who want to choose the best possible surgeon.”

Prior to this work, surgeons had to rely on their own sense of judgement - or the judgement of their patients - in deciding whether they had succeeded in creating a head shape that was 'normal'.

Potential

And there’s further potential for the LYHM, possibly going as far as to guide surgeons during the complex process of surgery, and being used to treat patients with injuries, or conditions other than craniosynostosis.

"There seems to be a relationship between one part of a skull or face and the rest of the skull and face," Mr Duncan says. “So even if only a part of the skull or face is intact, the model could be used to reconstruct what the rest of the face or skull should look like. It's very exciting, it is the only model of its kind that currently exists and there's a huge amount of interest in it."

A version of this article originally appeared in the York Press on 25 June, 2018.

The LYHM was developed with funding from Google, via its Faculty Research Awards Programme, The Royal Academy of Engineering and Leverhulme Trust, QIDIS and The University of York Centre for Chronic Diseases and Disorders.

The text of this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence. You're free to republish it, as long as you link back to this page and credit us.

Dr Nick Pears

Research Title: Senior Lecturer in the Department of Computer Science

Among Nick's areas of interest are computer vision and pattern recognition, in particular related to 3D imaging and 3D shape analysis.

Discover the details

Find out more about research in our Department of Computer Science.

Explore more research

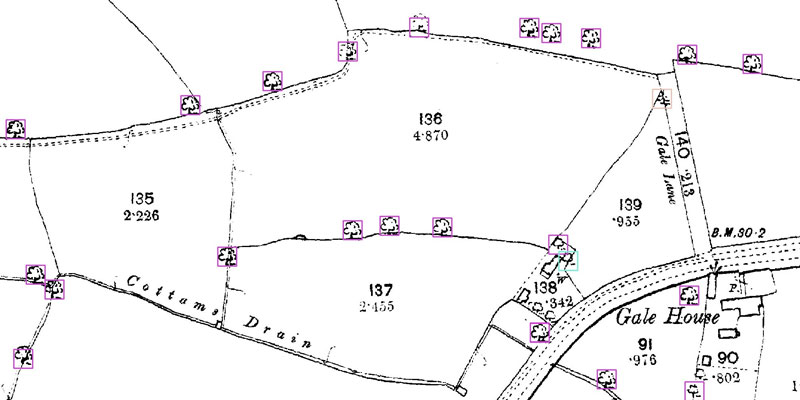

A research project needed to spot trees on historic ordnance survey maps, so colleagues in computer science found a solution.

We’re using gaming technology to ensure prospective teachers are fully prepared for their careers.

A low cost, high-accuracy device, could play a large part in the NHS's 'virtual wards'.