Lewis Walpole Library Visiting Fellowship Award Report

Posted on 3 October 2018

This summer I was delighted to be let loose for one month in the rich collections of the Lewis Walpole Library at Yale. Thanks to their Visiting Fellowship, I commence my third year of doctoral research with a vast array of unique visual material to support my literary enquiry into the role of horse-drawn carriages in Jane Austen’s novels, and the Georgian period at large.

Having only limited experience of archival research, I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t apprehensive about this venture – what is the most efficient way to navigate the LWL’s holdings? what is my research game plan? how do I avoid those oh-so-tempting research ‘rabbit holes’? and so on and so forth. After all, once you notice the proliferation of carriage and carriage-related images produced during the transport revolution, you cannot un-see it. Carriages will, without fail, turn up everywhere you look, turning your short-list of core images by artists such as George Stubbs and satirists Thomas Rowlandson and James Gillray into a daunting never-ending scroll of potential sources to explore.

My worries, though, were short-lived. Once I’d been given the tour of the library and was all settled in to the LWL fellows’ on-site accommodation, it was apparent that I would not be without support over the coming month. The catalogue staff and summer workers were always on hand to answer queries, often pointing myself and the other fellows toward some of the more obscure pieces in their collections, always with fruitful results. I realised, too, that the structure of my thesis doubled particularly well as a means of prioritising and working through the vast number of caricatures and prints that I intended to consult.

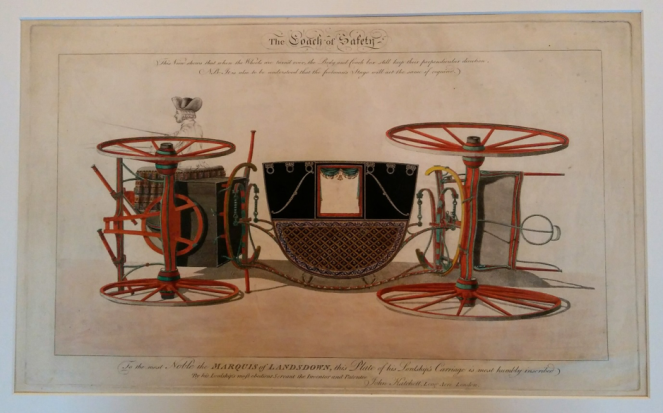

One piece that I kept coming back to repeatedly was ‘The Coach of Safety’, an elaborate watercolour design, finished with shellac and silver detailing, for an opulent vehicle created by the eighteenth-century’s most pioneering coachmaker, John Hatchett of Long Acre.

‘The Coach of Safety’ (1789). The dedication below reads “To the most noble the Marquis of Landsdown, this plate of his Lordship’s carriage is most humbly inscribed. By his Lordship’s most obedient servant the inventor and patentee, John Hatchett, Long Acre London.’

The print shows how the coach-body maintains its perpendicular orientation even when the carriage(the mechanical framework and wheels upon which the body is ‘hung’) is overturned. Carriage disasters were a common occurrence in the eighteenth century – even with the great improvements to roads and the adoption of Turnpikes – and were widely satirised in grotesque proportions in periodicals and prints. This vehicle, the likes of which I had never encountered before during my research, is testament to the great leaps in vehicular innovation compared to the simple and lumbering coaches of just 40 years previous.

Thanks to the wisdom of my supervisor, I have always been aware that my thesis would benefit from visual representations of carriages, but until working in the LWL I truly underestimated just how transformative it could be. Not only is my research more energised and vibrant, but my whole understanding of the cultural and political moment that I am researching has been strengthened and enriched. For me, the eighteenth century has been brought to life, in full technicolour detail.