Good Life with Dementia - Research Blog

What makes life with dementia better?

Friendship, sharing and a new perspective.

Kate Gridley, Research Fellow at the University of York, shares how a post-diagnostic dementia course co-delivered with peer-tutors helps people living with dementia.

“It's a scary thing to start with, but come on those courses and you won't be scared for much longer. You'll know what it's all about, and you'll have a different attitude towards it and take a different approach with it.”

[Tutor with dementia on the Good Life course]

Receiving a diagnosis of dementia can be scary. Often a whole host of different services and professionals are involved in assessing and breaking the news. But then what?

In the weeks and months following a diagnosis, people can face uncertainties, with nagging questions and no obvious place to go for answers.

People with dementia also report feeling ‘invisible’, as professionals (and other people in their lives) can talk over them, or past them, as they turn their attention to other family members or ‘carers’:

[Learner] “I have found that you can go places and you're not in the room. I don't know whether you understand that or not.”

[Researcher] “Is it that sense of feeling invisible?”

[Learner] “Yes.”

[Researcher] “Can you just explain how that makes you feel when that happens?”

[Learner] “Well, that makes me sad…”

[Learner with dementia on the Good Life course]

Most courses about life after a dementia diagnosis are run for carers and/or were designed by professionals. This was what led Damian Murphy (who works for Innovations in Dementia) to ask a group of people living with dementia: ‘What messages would you want to give someone recently diagnosed with dementia, based on your own experience?’ Their answers formed the basis of the first ‘Good Life with Dementia’ course, a co-produced course run by and for people with dementia directly, supported by Innovations in Dementia.

The University of York has been working with Innovations in Dementia, and three previous tutors with dementia (in partnership with Hull York Medical School, Tees Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust and Meri Yaadain) to learn more about this innovative approach to providing peer support and understand why this could be a helpful part of post-diagnostic support.

How the Good Life course works

People with dementia who took part in the Good Life with Dementia course told us that during the course they:

- Felt seen, valued and understood.

- Had fun and felt relaxed.

Looking to the future, learners and tutors appeared to:

- Gain social confidence and build lasting connections.

- Feel more able to face the challenges dementia presents.

To evaluate the Good Life course, a University of York researcher and a co-researcher with dementia observed two courses in 2023 and interviewed learners and tutors with dementia.

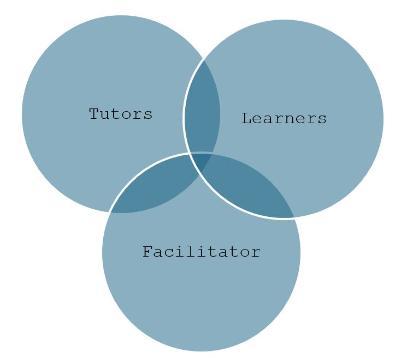

It’s likely that these outcomes aren’t guaranteed, as they depend on tutors, learners and the group facilitator all working together to co-create a safe space characterised by:

- Equality

- Shared experience

- Positive expectations

- A friendly, non-judgemental atmosphere.

In this context, we observed that people with dementia felt able to confront dementia, challenge negative stereotypes, learn from each other and find positive ways of approaching life with dementia. They also recognised and made social connections and realised they were not alone.

“…you can express yourself, or pick up on things, and use them when you get back home.”

[Learner on the Good Life course]

Building from the Good Life Course

We also wanted to understand how a course like this, which relies heavily on shared experience, could help people with dementia from diverse backgrounds. To explore this, we ran four focus groups with people with dementia and their supporters from South Asian communities.

These focus groups highlighted the importance of ensuring courses are welcoming to people from all different backgrounds and are approached with openness and ‘cultural humility’. People with dementia have a wide range of backgrounds and values, but those on the course will all share at the very least a diagnosis of dementia. What they share beyond that needs to be considered based on individual circumstances rather than cultural assumptions. In this context, it might be necessarily to think of what is shared beyond the apparent – cultures might be different, but the requirement for respect and validation, to be seen in the face of cognitive challenges, is arguably universal.

“People who have dementia, they should be given a similar type of person to them. They can help converse with them about dementia. My dad's a factory worker, he was a labourer all his life, he should be given someone who had that kind of a past to talk to my dad.”

[Focus group 3]

To achieve a safe space characterised by friendliness and equality takes skilful facilitation, and acknowledgement that what might be intended to be open and welcoming may not always translate in that way. Having tutors with dementia involved in co-designing and running the course could offer a bridge and might empower people with dementia to personalise the course for those in the room. The value of learning from one another across cultures and experiences, of finding where differences and similarities exist, was recognised as a potential strength of the Good Life model:

“It also would be good to know the experiences from other communities. Some communities they are affected more than others, like with COVID-19, the Asian community is affected most. Yes, they should get together […] that's okay, it could work.”

[Focus group 3]

Some people in the focus groups were concerned that making people with dementia tutors could put undue pressure on them. But being a peer-tutor doesn’t have to be a daunting prospect, with the right support from an experienced facilitator. Damian said he usually presents this as: “Do you want to help us with this course? You’ve got a lot to offer.” For the focus group members, being both supporter and supported was essential to the success of the peer-tutor role:

“I think, what do you call it, it would be good for them, but it would need guidance or support. So somebody, for example, the people who've got dementia could work through here doing it, but there should be somebody at the back observing and guiding them to do or say.”

[Focus group 1]

The focus groups concluded with some thoughtful optimism about the potential to bring the Good Life course to people from diverse backgrounds.

Where next?

Peer support for people living with dementia is recommended in policy. It can promote social inclusion and help people respond to a diagnosis of dementia.

The Good Life with Dementia course offers a promising approach. We will be using the research to develop a model that shows how the course could work, what the possible pitfalls are and how to avoid these. This should help others to run peer-led courses that enable friendship, sharing and hope for more people with dementia, whoever and wherever they may be.

“It's changed me. …For me, it certainly is a new beginning for me in my life, because I'm going different ways that I would never have gone before.”

[Tutor with dementia on the Good Life course]

To find out more about the Good Life with Dementia research, contact kate.gridley@york.ac.uk or visit the University of York Good Life with Dementia Research webpage