Dr Angela Hodge

Reader

Research

Nutrient cycling in soils and implications for ecosystem services

Soil provides many of the ecosystem services upon which humans depend from food and biomass fuel production to water and nutrient cycling and climate regulation via carbon sequestration. Yet, degradation of soil is occurring worldwide including through a loss of organic matter content. This is important as soil organic matter improves the water holding capacity of the soil, enhances soil particle aggregation and acts as a nutrient reservoir as well as a habitat for soil organisms.

A main focus of Angela’s lab is how nutrients from organic matter are recycled in the soil-plant system and the implications for plant nutrient acquisition in agriculture and natural systems. For example, nitrogen (N) is a critical limiting nutrient in many ecosystems. Plants capture N largely in inorganic form relying on microorganisms to release inorganic N during the decomposition of organic materials. However, most N is in organic form, often occurring as complex molecules. Furthermore, the distribution of these organic nutrient resources in soil is heterogeneous both spatially and temporally. Thus plant roots must locate and exploit these organic-rich zones or patches in order to acquire the nutrients contained within them and in competition with other members of the soil community, including the microbes that are processing the N and C forms.

|

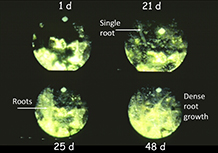

Fig 1. Development of roots of Lolium perenne in a patch of algal cell wall material added to soil. Roots were viewed over time using a borescope camera inserted into the soil profile. |

|

The majority of plant roots also form mutualistic symbiotic associations with mycorrhizal fungi, of which the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) are the most common type. We are investigating how AMF interaction with other members of the soil microbial community as well as the host plant in nutrient acquisition and organic matter cycling using both mechanistic and ecological approaches.

|

|

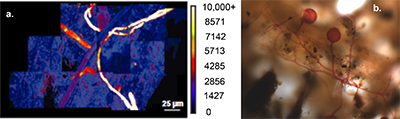

| Fig. 2. a. Composite of 14 NanoSIMS images of a Plantago lanceolata root colonised by AMF hyphae. The colour scale represents δ15N enrichment ranging from natural abundance (black) to 10, 000+ ‰ 15N (image taken by our collaborator Dr Jennifer Pett-Ridge, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, CA, USA) and b. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal hyphae with attached spores growing around a decomposing root in soil. |

Our goal is to better understand the complex dynamics of organic matter cycling in the soil-plant system with a view to enhance nutrient capture by crops while ensuring the soil system is managed in a sustainable manner.

Teaching and scholarship

![]()

My aim as a teacher is to engage students with the subject content to establish a firm foundation of knowledge from which to stimulate critical thinking and promote understanding.

![]()

Soils are an essential yet, often under-valued, resource. We will often admire the diversity of life that can be seen aboveground in the landscape with barely a second thought for the soil below. Yet, soils sustain this aboveground diversity and are themselves very diverse. As a soil biologist my lecture material is inspired by this wonderful world beneath our feet and attempts to bring the unseen complexity of interactions that occur in the soil environment to life. Soils are the most complex of all environments comprising a soil, liquid and gaseous phase. Moreover, root growth influences the physical, chemical and biological properties of soils at a range of scales, but most profoundly in their immediate vicinity, the volume of soil called the rhizosphere. My teaching therefore covers this broad range of scales, from single ion movement through to entire ecosystems; and covers topics, from plant-microbe interactions to meeting the challenges of ensuring food security.

![]()

My tutorials are under the broad heading of soil microbiology. We discuss various process in the soil that impact upon microbial activity and how this may, in turn, influence plants. In addition, and in common with my research interests, the influence of mycorrhizal symbiosis, a mutualistic symbiosis between soil fungi and the vast majority of plant species is also a topic of discussion. Tutorial sessions also give students the opportunity to practise presentation skills, learn how to critically evaluate the published literature and obtain feedback on their written work.

![]()

Projects offered are aligned to the on-going research conducted by my lab group. However, there is also a degree of flexibility within project topics so that the interests of the student are taken into consideration and ideas and hypotheses on the project direction are encouraged. The sort of techniques and skills the student will learn are firmly founded in physiological ecology, microscopy and chemical analysis.