Don't forget to pick up after your wolverine!

Posted on Tuesday 2 July 2024

Those who pay attention can find prints trailing through the forests, the countryside, even in cities, skulking through gardens and circling rubbish bins – interspersed with the individual calling cards of the animal in question: their poo. These traces are a testament to growing populations of wild mammals across the continent, including beavers and wild boar, as well as bears, wolves and wolverines. This trend is welcomed from a policy perspective, since the EU has made binding commitments to restore its nature and wildlife.

This trend, and the poo, was also the reason I found myself perched atop a snowmobile in Swedish Lapland, trying hard to keep up with the ranger who was roaring ahead in the distance while avoiding knocking myself out on a tree branch. Our task of the day: finding wolverine scats by following their footprints across mountains and through forests, in temperatures shy of -20 C, was not easy. However, the effort is crucial to ensure that the costs of living with these predators can be fairly redistributed.

Tagging along with a Norrbotten county ranger to collect wolverine scats. They are then sent by regular mail to a lab where the DNA is extracted and matched to individual wolverines. Wolverines are only about 35-45 cm high but have massive paws, enabling them to travel on top of the snow and, when the conditions are right, to take down both reindeer and moose.

Redistribution has become an urgent matter, because the flipside of wildlife restoration is that some species are difficult neighbours. The industrious beavers may flood fields and forest plantations, and the boar can ravage painstakingly planted fields in a matter of hours. The return of large carnivores, meanwhile, may mean that livestock left grazing on a hillside are no longer there the next morning, and render beloved forest paths suddenly feeling unsafe to local people. Additionally, the claimed benefits of their return tend to be slow (if at all) to materialise and rarely benefit the locals, while the disbenefits are instant and dramatic. This has created widespread “NIMBYism” toward species such as wolves – eg “Yes we should have them, but Not In My Backyard”.

NIMBYism is a well-known phenomenon for many “goods” that we need and want as a society, including windmills, infrastructure, and national parks. Various tools have been devised to counter the issue and redistribute the costs and benefits of such goods, including direct payments to those faced with living with(in) or near them. These payments can work as an incentive to increase local acceptance, mitigate harm, or help people adapt their livelihood. Yet in the context of conservation, these types of payments are still relatively new, and we know little about their implications for local people. This is the focus of my research project at LCAB. It explores a scheme in which Sámi reindeer herders are paid a sum every year to coexist with wolverines and lynx. The sum is based on the number of carnivores within their herding territory, distributed yearly by the Swedish government. It is the oldest scheme of its kind in the world, and the one of only a few funded by a state rather than an NGO. According to a 2015 study, based on data from its launch in 1996 until 2011, the scheme has been successful in increasing wolverine numbers. But is this still the case? And what about the recipients, do they think the scheme is working?

The opportunity to explore these questions came about as the Swedish Environment Protection Agency together with the regional managers decided to test a new method of estimating the Norrbotten Conty’s wolverine population: from counting den-sites to identifying individuals through the DNA in their scats. The idea was that both rangers and the herders, who know the territory better than anyone else, would collect the scats during the snow season, ensuring the whole area was properly sampled.

Reindeer herders in traditional attire at the Jokkmokk Market, one of the most important Sámi events of the year. There are around a thousand professional reindeer herders in Sweden, who manage their own reindeer and those of family members, following the herd as it moves from the east to west and back again with the change of the season.

Trustworthy monitoring, and an appropriate estimate of what the carnivore is worth, are preconditions for this type of scheme to work and be considered fair, because without knowing how many and where the wolverines are, the state cannot pay the right amount to the right people. In the past decade, changing snow and weather conditions have made den-site monitoring unreliable, and a recent report found that stakeholders don’t trust the results. Paired with significant underfunding of the scheme, it has led many herders to lose faith in the Swedish carnivore policy. The institutions hope the new method will lead to increased trust in the data, enhanced local participation, and improved funding allocation, ultimately increasing coexistence capacity in the area. My job is to find out to what extent these hopes have been realised, an exciting opportunity to inform whether and how the DNA method will be rolled out also in other areas of the country.

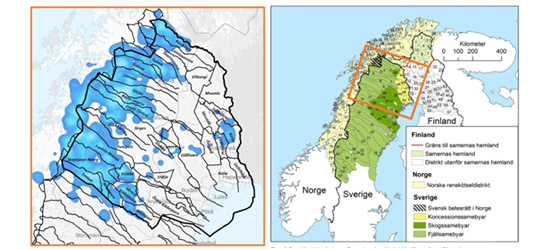

Norrbotten County (left) with the estimated wolverine distribution marked in blue and its 32 reindeer herding communities outlined in black. The reindeer herding district (marked in green on the right) covers about 50% of Sweden. Images courtesy of Norrbotten County and Sametinget.

In addition to trying my hand at poop-collection, my field research has consisted of taking part in meetings between the reindeer herders and the County staff before the monitoring season started; interviewing herders, rangers, and institutions during the season and; distributing a questionnaire after the season was completed to assess the trustworthiness of the results.

At the moment of writing this entry, I am not able to provide any answers. I have just plonked myself back down at my desk after the last field stint, with an intimidating yet exciting pile of data to churn through. It will hopefully be cajoled into the shape of a report by the end of the summer and a few collaborative publications by the end of my project. So stay tuned, I cannot wait to tell you more.