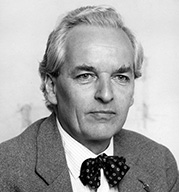

Sir Andrew Derbyshire

'A work of genius'

The development plan was published. It was a remarkable document - ‘a work of genius’ in the words of Sir Ron Cooke, a later Vice-Chancellor - and highly respected not only in the University but in the architecture community to this day. Not simply a functional plan, Derbyshire extended it to embrace a number of additional functions which he thought the University should achieve. ‘These’, he said, ‘were to provide an environment in which young people would feel comfortable – not overwhelmed by the size of the institution, but at ease with themselves and one another; in relation to the unit as a whole. And secondly that it should provide the basis for a meeting of minds.’

So the plan started from first principles: what should a university be, how should it grow, how do its activities interact, how do people move about? Derbyshire wanted it to be a memorable place in which the relationship between landscape and buildings was absolutely fundamental.The distinctive covered walkways also stem from this plan, providing a physical as well as metaphorical link between buildings, and also crucially leading through the buildings, promoting informal contact. Even members of the public could walk through and observe students working in glass-walled science laboratories.

The original development plan

Building begins

RMJM were appointed as the architects for the construction with a strong team, including Bob Owston, Colin Beck and Bill Bordass. The ideals articulated in the plan were destined to be delivered through a series of pragmatic decisions about construction. As always, budget and time were key considerations. The initial building programme was to be very fast – the first students were due to arrive in October 1963.

The response was to use a form of building developed by a consortium of local authorities for schools, called CLASP. Although it had never been used on this scale, Derbyshire recognised its advantages in this context. The buildings had slab foundations (good on marshy land) and steel frames, which were quick to erect. Then prefabricated panels were used as exterior cladding with prefabricated interior walls also connected to the frame. Prefabrication, a solution proposed by Johnson-Marshall, allowed for much of the building work to be done off-site and elsewhere in the country: it could happen quickly and was not reliant on an under-sized local workforce. Modular buildings were also flexible to allow for growth and expansion.

The lake was designed to cope with the run-off from the new buildings and hard surfaces and to help drain the very marshy site. It could have been a concrete tank, but Derbyshire’s design made it a beautiful addition.

The University opened its doors to students on time in 1963. Derbyshire was to continue working on delivering the plan for ten years. Later he was invited back by Vice-Chancellor Sir Ron Cooke, to act in an advisory capacity, and sat on the Estates and Buildings committee.

The development plan was revisited in a major way when planning for the University's Campus East expansion was initiated in 2003. The original principles for development were re-examined and found to be valid and relevant still in a new millennium.

They were restated, updated where required and the key features of community and landscape adopted as the heart of the proposed development. This time the ‘community living and working together’ was expressed as not just an inward-looking community of scholars, but explicitly embracing our external partners, collaborators, neighbours, friends and supporters.

A remarkable life

Andrew Derbyshire was born in 1923, and grew up in Chesterfield. Sandwiched between the Peaks and great houses such as Chatsworth on the one side and the coal fields and iron works in the east, it was somehow a meeting point between the humanities and sciences and a source of his later belief that arts and sciences needed to combine. After attending the local grammar school he went to Cambridge where he read a Natural Sciences Tripos.

From childhood he had always wanted to be an architect. After the War he sought the advice of Richard Crossman and went to work at the Building Research Establishment, then won a scholarship at the Architectural Association. Here he learned the importance of good management and interdisciplinary working.

Politically active and a pacifist, he wholeheartedly supported the welfare state and believed that it should be supported by architecture. The best support that architecture could give was in the public sector – to him and his colleagues private practice was at that time anathema. As public servants, architecture could be part of the ‘big society’.

Derbyshire’s first job was at Hertfordshire County Council, with his future partner Stirrat Johnson-Marshall. Here he was involved in building a power station, prefabricated in aluminium, glass and steel. He returned north and worked on schools projects in West Yorkshire. In 1955 he joined Sheffield as Deputy City Architect and designed Castle Hill Market among other work.

It was from there that Derbyshire joined Robert Matthews Johnson-Marshall in order to work on the new University of York. In 1964 he became a partner in the firm, then Chairman in 1983, and President in 1989. In 1982 he lost the presidential election of RIBA, a source of great disappointment to him.

However, public recognition came when he was rewarded with a knighthood in 1986. During his career, he was a non-executive director and advisor to a number of boards and organisations, and a visiting professor at the universities of Leeds and York. He retired in 1998.

Andrew Derbyshire retained an interest in and strong sense of identity with the University of York’s ideals and its continuing development and growth. Equally, York continues to acknowledge the great debt it owes to him for his inspirational contribution in making the University the place it is.

Sir Andrew Derbyshire died on 3 March 2016. He is survived by Lady Derbyshire, three children including his architect son Ben, and numerous grandchildren, great-grandchildren and step-grandchildren. Our sympathies are with his family and friends.

Elizabeth Heaps

Former Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Estates

May 2016